If you’ve been a thyroid patient for any length of time then I’m sure you’ve run into the frustrating problem of trying to convince your doctor that your symptoms are, in fact, related to your thyroid.

Over the years, thyroid patients have repeatedly asked me why is it that their doctor seems so reluctant to even entertain the idea that their thyroid may be the cause of their symptoms when their TSH is normal.

My answer is always the same:

It has to do with the current thyroid treatment paradigm (1).

And explaining the paradigm is this easy:

If your doctor believes that you have a thyroid problem then he or she will check your TSH.

If your TSH is anywhere within the normal range then your thyroid is considered ‘normal’ and whatever you are experiencing must be caused by something else.

Everything that your doctor says and recommends should be evaluated through this lens.

The problem?

There’s really no scenario in which we can distill the complexities of thyroid function down to such a simple algorithm.

Thyroid function is regulated at so many different levels (2), is impacted by so many different systems (3), and requires the optimal function of other organ tissues (4) to operate smoothly.

Dysfunction in any of these areas can cause problems and symptoms that simply won’t be detected by standard TSH testing.

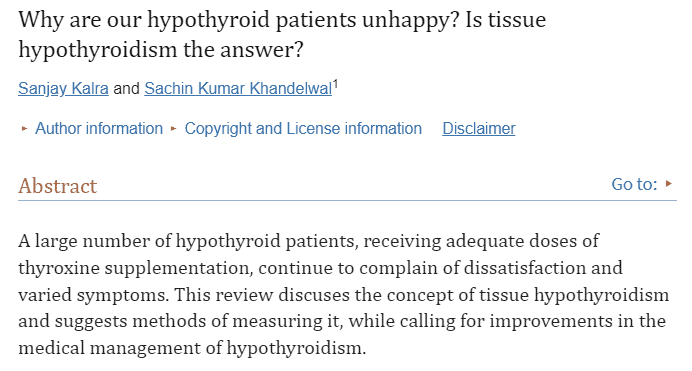

And guess what? Even the most die-hard conventional medicine advocates know that this is true.

They may disagree with what the integrative community says should be the proper way to manage thyroid disease but they at least recognize that there is a problem (5).

This has led us to our current situation:

A Tale of Two Models: Alternative Thyroid Treatment vs Conventional Thyroid Treatment

On one hand, we have conventionally trained doctors (primarily endocrinologists and primary care physicians) that advocate for the simplistic TSH model of managing thyroid disease.

On the other, we have the alternative (integrative and functional) thyroid approach to managing thyroid disease which includes factors beyond TSH testing.

Both approaches have their merits but each side can take it too far.

On the conventional side, doctors can appear obstinate and unwilling to budge or entertain ideas and recommendations that stem from alternative blogs found on the internet (like mine).

On the alternative side, doctors and patients can tread into uncharted and untested territory including recommending treatments that have never been proven to be effective or, worse, may be dangerous.

In a strange cycle, as the conventional side digs in its heels it pushes the alternative side down a path that leads to more aggressive and untested treatments.

And this is really where we find ourselves right now.

You can pretty much guarantee that your endocrinologist is unlikely to look beyond the TSH and you now have a huge number of alternative thyroid experts that are recommending therapies and treatments that probably shouldn’t be recommended.

So what can we do to bring more balance to this tug of war and bring us closer to the center?

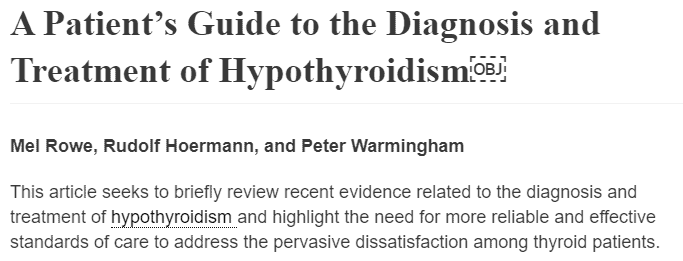

One approach would be to provide conventional doctors with a set of sound and thoughtful treatment recommendations that are based on science to replace the current treatment guidelines.

This paper does just that and it was brought to my attention by Paul Robinson.

It outlines some common sense treatment recommendations that allow a more comprehensive evaluation of the thyroid without stepping into the untested and potentially dangerous territory that may be recommended by online blogs and thyroid groups.

Below you will find these recommendations (which are also found in the paper link above) with some commentary.

Let’s jump in:

DOWNLOAD FREE RESOURCES

Foods to Avoid if you Have Thyroid Problems:

I’ve found that these 10 foods cause the most problems for thyroid patients. Learn which foods you should avoid if you have thyroid disease of any type.

The Complete List of Thyroid Lab tests:

The list includes optimal ranges, normal ranges, and the complete list of tests you need to diagnose and manage thyroid disease correctly!

#1. Diagnosis must always include a patient’s full medical history.

Getting a full medical history and doing a comprehensive physical exam have been staples of good medicine (6) since their inception.

A good comprehensive medical history is especially important for thyroid patients.

Why?

Because by providing a detailed history, doctors have the potential to identify the cause of thyroid disease, ascertain which thyroid medications may be ideal for you, whether or not your thyroid disease is your primary issue, and what type of thyroid problem they know to look for.

Due to the nature of the non-specific symptoms that hypothyroidism can cause, it’s not uncommon for people to believe that they have a thyroid problem when they really don’t.

I’ve lost count of the number of people who are confusing conditions such as menopause, for instance, with hyperthyroidism.

Or the number of patients who have caused hypothyroid-like symptoms from extreme diets and caloric restriction.

These conditions can result in symptoms that mimic those of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism but their treatments are not the same.

As a patient, it’s also important for you to be able to provide a detailed history with pertinent information that is helpful for your doctor.

It’s the doctor’s job to make sense of it, but it’s always easier to make sense of something that is coherent!

And in the current healthcare environment where time is a novelty, providing succinct and structured information to your doctor can be very beneficial to you!

More meaningful information means a faster diagnosis and better management of your condition.

#2. Diagnosis must include an evaluation of symptoms, which reflect tissue thyroid responses, and the patient’s well-being.

This is an important point that is often missed by the conventional TSH approach to managing thyroid disease.

In the TSH paradigm, if the TSH is normal then thyroid function is normal throughout the body.

For whatever reason, the assumption is made that if the TSH is normal then all tissues in the body must have an equal and sufficient amount of thyroid stimulation.

But we know that this isn’t the case.

Different tissues in the body have different sensitivities to thyroid hormones based solely on the presence or absence of thyroid-activating and thyroid-deactivating enzymes (7).

We also know that tissues such as the heart (8), interact with thyroid hormone differently than other tissues.

This section is basically suggesting that if hypothyroid symptoms persist after normalization of the TSH then, perhaps, something else is being missed.

This opens the door to individual management of free thyroid hormones and their impact on thyroid symptoms.

Here’s why this is important:

If you take any thyroid medication (even T4-only thyroid medications like levothyroxine), it will bring down your TSH on a dose-adjusted basis.

But lowering the TSH isn’t necessarily helpful if your body is not taking the T4 thyroid medication that you are giving it and activating it.

This is why the presence or absence of these thyroid-activating enzymes (known as deiodinases) needs to have some place in the management of hypothyroidism.

This section allows for just that.

#3. Where symptoms indicative of thyroid disease are present, an ultrasound of the thyroid is advisable.

Thyroid patients are usually accustomed to thinking about the importance of blood thyroid levels but there is some benefit to physically looking at the thyroid gland.

An ultrasound is a cheap and effective way to do just that.

It allows the visualization of the thyroid gland which has the potential to identify physical abnormalities in the form of nodules, goiter, and inflammation.

This is important because conditions such as early-stage Hashimoto’s can cause low thyroid symptoms without abnormalities in serum levels of thyroid hormone.

Identifying this problem early allows you to get a headstart on treatments which typically means better long-term outcomes.

#4. Symptomatic testing and case finding should include TSH, FT4, and FT3, arguable Reverse T3, TPO ab, and TG ab (only if TPO is negative and TSH is high).

This is pretty standard and something that everyone reading this should be familiar with.

TSH testing by itself does not provide a complete picture of thyroid function but adding in some basic tests such as free thyroid hormones in the form of free T3 and free T4 will provide a better picture.

Testing for free thyroid hormones should be standard because it’s standard for just about every other pituitary-controlled hormone in the body.

For instance, when your doctor wants to check your estrogen level, he/she doesn’t order your FSH or LH, they check your estradiol.

The FSH and LH would be equivalent to TSH in this analogy.

If your doctor wants to check your testosterone level, he/she doesn’t order your FSH/LH but, instead, orders your free and total testosterone.

If your doctor wants to check your cortisol, he/she doesn’t check your ACTH level, they check your serum cortisol.

For reference, testosterone, estrogen, cortisol, growth hormone, and thyroid hormone, are all regulated in a similar mechanism by both the pituitary and hypothalamus.

For reasons unknown to me (and believe me, I’ve looked), the thyroid is the only hormone that we check the pituitary releasing hormone instead of the actual free thyroid hormone level.

For this reason, free thyroid hormones in the form of free T4 and free T3 should be assessed in conjunction with TSH.

Whether or not to test reverse T3 is another issue which is why I think the recommendation here to possibly include it makes sense.

There’s a lot of pushback from the conventional side when it comes to reverse T3 and there’s not a huge amount of evidence to suggest that it’s helpful.

I can even tell you from personal experience in testing it on hundreds of thyroid patients that it’s not as helpful as many people believe.

So in this sense, it’s probably not worth the fight if your doctor is already willing to order both free T3 and free T4.

The inclusion of thyroid peroxidase antibodies with the exclusion of thyroglobulin antibodies also makes sense here.

TPO antibodies track much more closely with Hashimoto’s and hypothyroidism (9) compared to thyroglobulin antibodies and getting extra antibody tests that are unnecessary may just cause confusion.

Thyroglobulin antibodies can be elevated in cases of Hashimoto’s but it’s much less common compared to TPO antibodies.

Overall, these are sound recommendations that definitely meet in the middle between where the conventional side sits and the alternative side when it comes to thyroid lab tests.

#5. To avoid false test results (4), thyroid hormone medication should not be taken until after blood is drawn.

Many thyroid patients don’t realize that you can basically force your thyroid lab tests to show whatever you want depending on when you take your thyroid medication.

If you wanted your free T4 to be high, for instance, then all you have to do is take your dose of levothyroxine a few hours before you plan to get your thyroid labs tested.

This high level doesn’t give you any meaningful information, though, which is why you need to take this into account when you get your labs checked.

The advice given here is what alternative doctors have been practicing when it comes to testosterone replacement therapy and HRT for years.

The idea is to check your thyroid lab tests at their lowest point prior to when you get your next dose.

Here’s how it works:

When you take a dose of levothyroxine it will immediately surge in your blood until it reaches an apex.

Once it reaches its apex it will then slowly decline until you take your next dose.

If you didn’t take your next dose then the impact of that medication would eventually fade down to zero.

But your goal is to take your next dose before that happens.

By doing this, you are allowing a sustained level of thyroid hormone to remain in your body to help manage your symptoms.

This dosing schedule is completely different from the normal release of thyroid hormones from a healthy thyroid gland, though, which should be taken into account when evaluating thyroid function.

One easy way to do this is by checking your thyroid lab tests right before you are scheduled to get your next dose (roughly 24 hours).

This will help you avoid inaccurate thyroid lab tests which will only serve to confuse both you and the doctor.

#6. Multiple symptoms typical of hypothyroidism, accompanied by low FT4 and FT3 levels, are strongly indicative of hypothyroidism (5). Both FT4 and FT3 levels should be individually monitored and increased as needed to relieve symptoms of hypothyroidism, without creating symptoms of hyperthyroidism.

This section seeks to solve the problem that many thyroid patients face where they continue to experience low thyroid symptoms despite having a normal TSH.

This exact situation is often caused because even though the TSH level is normal, one or both of the free thyroid hormones are low.

This recommendation suggests that the presence of low free T3 and/or low free T4, in combination with hypothyroid symptoms, is strongly suggestive of hypothyroidism regardless of what the TSH shows.

This is where conventional doctors will have to step out of their TSH mindset if they want to solve the persistent hypothyroid symptoms that plague many thyroid patients.

The language here subtly suggests that the free thyroid hormones play more of a role in regulating thyroid status in the body than the TSH without overtly stating it.

This very problem is where the alternative side can take it too far, though, so caution must be exercised.

If you focus solely on the free thyroid hormones and exclude the TSH entirely, it’s very easy to take too much thyroid hormone in an attempt to ‘optimize’ your free thyroid hormone levels.

This can be problematic and may absolutely lead to problems for some patients down the road.

A nice compromise would be to continue to use TSH testing in concert with free thyroid hormone levels, and hypothyroid symptoms, while also recognizing that other factors may be contributing if optimizing your thyroid hormone levels fail to resolve all of your symptoms.

Based on this recommendation, you can use the symptoms of hyperthyroidism as an upper threshold for when you’ve taken this concept too far.

If you continually increase your dose of thyroid medication to try and push your free thyroid hormone levels higher, to the point that you experience hyperthyroid symptoms, then you know you’ve gone too far.

If you still remain symptomatic at that point, then you can be fairly sure that whatever symptoms you are experiencing are probably related to some other problem and not your thyroid.

Be careful not to get what I call thyroid tunnel vision when thinking about your dose of thyroid medication.

Thyroid tunnel vision is the idea that all of your ailments stem from your thyroid and in order to resolve them you must continually push your thyroid medication dose higher and higher.

It’s typically rarely ever the case that your symptoms are caused solely by your thyroid which brings us to the last point:

#7. Cortisol, Vitamin D, B12, and ferritin should be considered and also optimized for symptom relief.

This is another deviation from the standard and conventional advice but a welcome one.

Pretty much every alternative thyroid doctor out there knows just how important these other factors are because of how they indirectly influence thyroid function.

The function of cortisol and thyroid hormone, for instance, shows a strong correlation (10) with one another.

As TSH rises, cortisol tends to fall.

Testing for vitamin B12 is also another thoughtful recommendation due to how hypothyroidism impacts the absorption of B12 in the intestinal tract.

As a result, many patients with hypothyroidism end up with sub-optimal or grossly deficient vitamin B12 levels (11).

And, lastly, ferritin, as a marker of iron levels, is important for the production of thyroid hormone in the thyroid gland.

We also know that thyroid dysfunction leads to alterations in ferritin levels (12) which appears to be bidirectional in that low ferritin can lead to hypothyroidism and hypothyroidism can lead to low ferritin.

Testing for these deficiencies is important because their presence may be a sign of early thyroid dysfunction or, worse, contribute their own set of symptoms which can cloud your diagnostic picture.

Final Thoughts

I’m a big fan of promoting information that stands to help improve the outcome of thyroid patients.

I believe this set of recommendations does just that.

It provides you with a great tool that you can use the next time you go and see your doctor.

It’s easy for your doctor to dismiss a random blog article but it’s more difficult to dismiss a set of structured guidelines produced by knowledgeable experts and backed by scientific literature.

Hopefully, the commentary above also provided you with a better understanding of how conventional doctors think about thyroid disease.

Once you can better understand how they think about this disease state, you can then start to formulate meaningful questions and counters to their objections.

If you can do that in a nonadversarial way then you are well on your way to managing your thyroid condition!

And lastly, if you find yourself in a situation where your current doctor isn’t willing to entertain these recommendations or guidelines then your next step would be to seek out a second opinion or to find someone who is more open-minded.

Now I want to hear from you:

What do you think about these treatment recommendations?

Are you planning on bringing them up with your doctor the next time you go in for a visit?

Do any of the recommendations not make sense to you? Why or why not?

Where do you get most of your thyroid information from? The internet, your doctor, or some other source?

Leave your questions or comments below!